I’ve been to a number of raucous public hearings and meetings in Victoria and Saanich over the last few months. Something stood out to me—more than a few opponents to increased density and more housing called pro-density and pro-housing speakers “sadly misled” or “developer stooges.” There was a lot of nodding from these opponents when speakers talked about how new development is always unaffordable.

In my mind, proponents and opponents of density were completely talking past each other.

I want to challenge this phenomenon, but perhaps not in the way you might expect, with facts and figures. From what i’ve seen, the density debate is fundamentally about values. In other words, folks on either side of this density discussion simply have different visions of what their region can and should look like. If we recognize that the discussion is about values, we can have a better, kinder, and more honest discussion.

Value 1) Green space, the environment, and shading

One of the most common refrains I’ve heard at public hearings and meetings is that denser housing will mean the destruction of green space. This is true, if you define green space as backyards for single-family homes. I think anti-density folks understand exactly this— I heard “I believe in Nature In My Backyard” repeatedly.

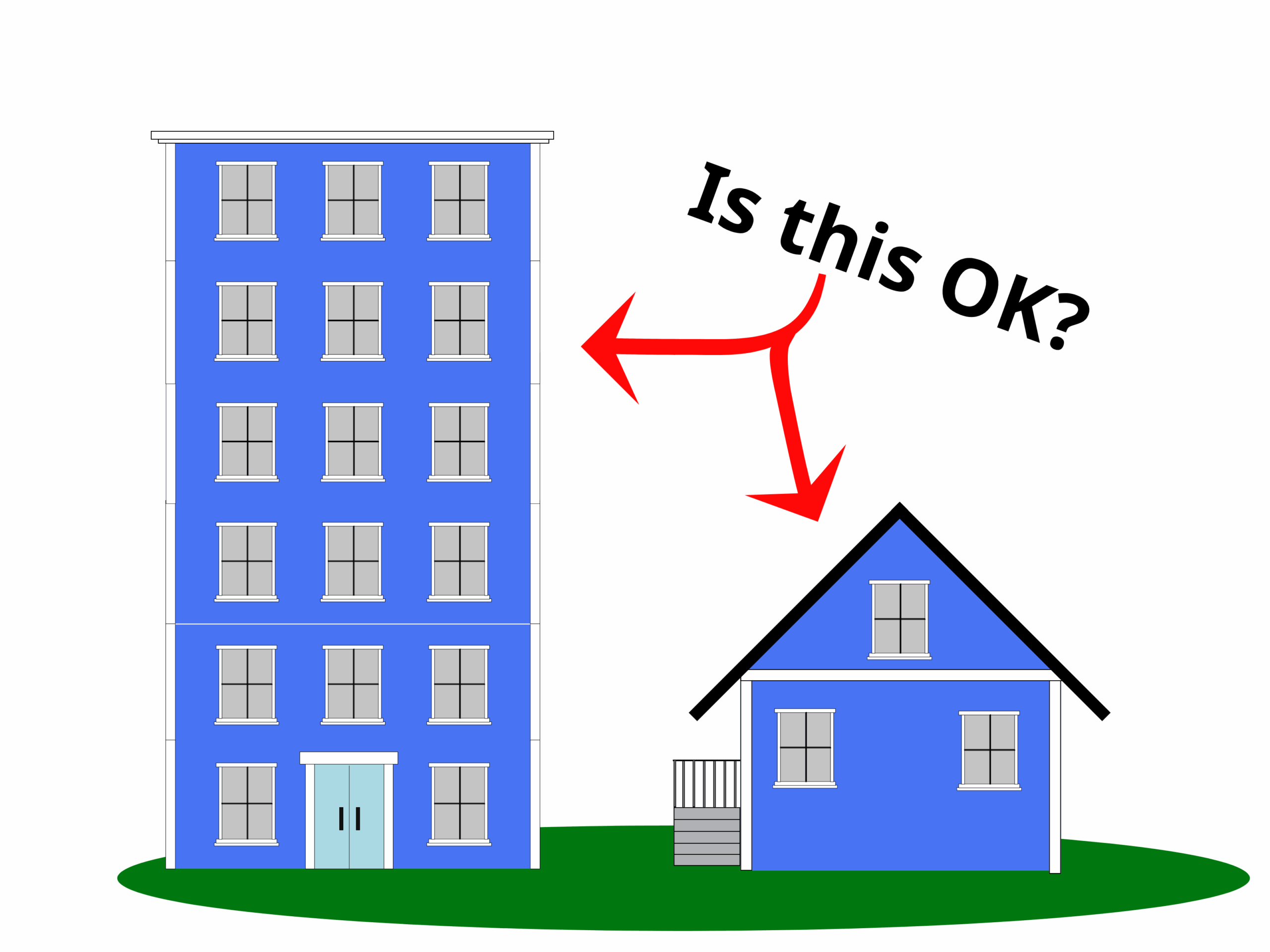

The key variable in this question is height. If municipalities allow taller buildings, communities or homebuilders can use the areas around those buildings for green space. For example, here’s what a building with six to twelve family homes could look like, if they were legal to build:

In this concept the apartments occupy about the same amount of space on each property as the single-family homes around them. That means no change to green space. If municipal rules force homes to be shorter, that means losing green space.

We should also consider that height is no exception to the rule that everything is a tradeoff. Taller buildings make backyards less private, and shade some previously sunny areas (although some residents might welcome some shade during summer heatwaves). While there are ways to mitigate these effects (well-placed trellises and awnings, bright façades, etc.) this is always a tradeoff of density.

While the introduction of more apartments and townhomes means everyone can have a backyard, these new homes bring more opportunities for creating parks and parklets, converting unused road space to trees and greenery, and, with good planning, constructing perimeter blocks (apartments on the outside, a park in the middle). In other words, density provides an opportunity to create more public spaces and amenities.

Something else to consider is the value of green space outside of your immediate neighbourhood. While the majority of the Core area of the Capital Region has seen very little change over the past two decades, the Westshore has doubled in size, largely at the expense of forestlands. You can see the process over time here, courtesy of Leo Spateholz. Ecologically, it would have been far better to keep those forests intact, and instead allow higher density in the Core.

So here are three value questions: what is more valuable, private or public space? What’s more important, green space or height? Is more shade and less privacy an acceptable tradeoff if it means getting more attainable homes? What’s more valuable, the appearance of your neighbourhood, or forests 10km away?

Value 2) Affordability, attainability, and profit

Affordability is one of the trickier things to talk about, because the actual term “affordability” can mean a dozen different things. Can young buyers “afford” homes built in 2025? Not right now, but we can hope to attain those homes in a decade or two, once those homes aren’t priced as new.

As a concrete example, when you look at rentals right now, 1980s rentals are going for about the same price as rentals built in 2010 (about $2300 all-inclusive for a 2 bedroom rental). In other words, “older housing” can mean anything older than about 15 years.

New home construction also helps lower rents. People who can afford new homes are currently living in older homes. When they move into new homes, their older homes are now available, allowing people to move in.

There’s something important to consider here. Homebuilders are selling new homes for higher prices because people are willing to pay more for a new home, but also because homes are extraordinarily expensive to build, especially when factoring in fees and delays imposed by local governments (sometimes more than 4 years of delay for a small apartment building in some local municipalities). In other words, homebuilders need to price their new-built homes to make a profit. In fact, if they don’t, banks won’t give them a loan.

This profit makes a lot of people very uncomfortable, and I completely understand why— someone is making money by changing your neighbourhood. This concern is part of why we have extremely strong local government rules against homebuilding.

Someone does always profit from a crisis, however, and in the case of the housing crisis the people profiting are those who were able to buy homes and build incredible amounts of equity.

Here are the value questions: is it acceptable that building new homes might lower the value of existing homes? Is it acceptable that homebuilders price these new homes higher, as they are new? Is it acceptable that someone might make a profit on building a home, if it leads to more attainable housing in the future? What is different about profit made by a developer vs profit made by someone selling their first or second property?

Read more on how building new housing lowers prices:

I think it might be worth talking a little more about how new housing leads to more affordability

Picture a retired couple wanting to downsize and move to a neighbourhood where they can safely age in place. They want to buy somewhere without any “surprises” behind the walls, where they can walk to a coffee shop, and where they can reliably take public transit, since neither of them can drive at night anymore due to deteriorating eyesight.

Say they purchase a new condo. They move out of their mid-century four-bedroom single-family home, which is then purchased by a mid-career couple wanting to start a family. That mid-career couple was renting the top half of a house, which can now be rented by a pair of friends happy to move out of their illegal basement suite. This suite can now be filled by young students, who are happy to be able to move out of their parents’ house.

If that condo doesn’t exist, where does that retired couple move? Maybe they look for a similar family home closer to transit. That means they are competing for the same kind of home as the mid-career couple. If prices lock out the mid-career couple from buying, they are stuck in the same market as the friends looking for a larger rental. If the friends can’t afford a larger rental, they are stuck competing with the students for smaller and crappier rentals.

Economists refer to this phenomenon as a “Vacancy Chain”, and have studied it extensively. If you want to read more, see the Housing LIN and CHMC factsheets. You can also see peer-reviewed studies from the VATT Institute and the American Economic Review, among many others.

The argument against this is that for every home built in BC, there are thousands of people wanting to move from Toronto. While that might be true, that misses that thousands of people are already coming to BC from all over the world, and they participate in filtering just like everyone else. Every home counts.

The key thing to understand is that a millionaire from Toronto who wants to move to Victoria is going to do it regardless. The question is, can that millionaire buy a new home, or will the millionaire outbid a current resident and move into an existing home?

Value 3) Traffic and the environment

Another area of consistent pushback is around parking and car ownership being harder to manage in dense areas. But here’s the thing—while it doesn’t work for everyone, a lot of people don’t want to drive daily or own a car at all, and each person choosing a different option than driving means fewer cars on the road. Denser housing supports living car lite or car free far better than suburban sprawl. And things like underground parking are extremely expensive, as much as $100,000 per parking stall, which directly increases the cost of a home.

There are a lot of reasons why you might want to go car-lite or car free in a denser area. Living where you can walk, bike, or take transit to services and work means you spend less on transportation. Even if many people living in denser areas still choose to own a car or use carshare, the option to walk to the corner store to pick up eggs, or bike to see friends, or take the bus to work, saves each person thousands of dollars in gas, insurance, maintenance and depreciation, especially if a two-car household can transition to being a one-car household. BCAA has a great calculator for these costs which is worth checking out.

Read more on car ownership

Several people I know think of owning a car as equivalent to being free. That common idea is a product of transforming Canada into a country without viable alternatives to travel (allowing railroads, intercity buses, and steamship lines to fail, changing investment from rail into roads).

As a general question, does car ownership mean freedom, or is being free more about the ability to travel in the way that you choose? I and many others have found freedom through a combination of cycling, public transit, and carshare.

Besides just cash, the time you get back from being closer to services and jobs is also important to many people. Shorter commutes means more time available during the day. Walking and biking also have key health benefits. In contrast, sitting in traffic is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular diseases. Denser living also leads to more efficient home heating, fewer GHGs from driving, and fewer forests cut down for sprawl. It also protects farmland from development pressures.

Here’s the value question: is it acceptable to build a city where driving is not the default way to get around?

Leave a Reply