In November 2024, just over a thousand residents from some (but not all) of the University of British Columbia (UBC)’s neighborhoods of permanent residents headed to the polls in what looked a lot like a municipal election, complete with an all-candidates’ forum, campaigns, and voting stations.

However, the body that they elected — the University Neighborhoods Association (UNA) Board of Directors — is not a local government. It does not have the powers of a local government, and does not provide most of the services a local government would.

Other residents at UBC who live in the vicinity do not get to vote in this election, and neither do the nearly 14,000 students who live in on-campus housing. Why does this strange jurisdictional gray area exist? Ultimately, it comes down to the rather tangled answer to what sounds like a simple question: What city is the UBC Point Grey campus in?

One might think that the answer is simple: Vancouver, of course. After all, UBC is located right next to the city and does not border any other municipality, and indeed the mailing address of any building at UBC quite clearly says “Vancouver, BC” on it.

Legally, it is not part of Vancouver at all. Vancouver City Council does not make any legislation that applies west of Blanca Street, and people who live there cannot cast votes in Vancouver’s civic elections in return. The lone exception to this is the Vancouver School Board, which residents can vote for like anyone who actually lives in Vancouver.

Municipal services are provided by a hodgepodge of local, provincial, and even federal agencies.

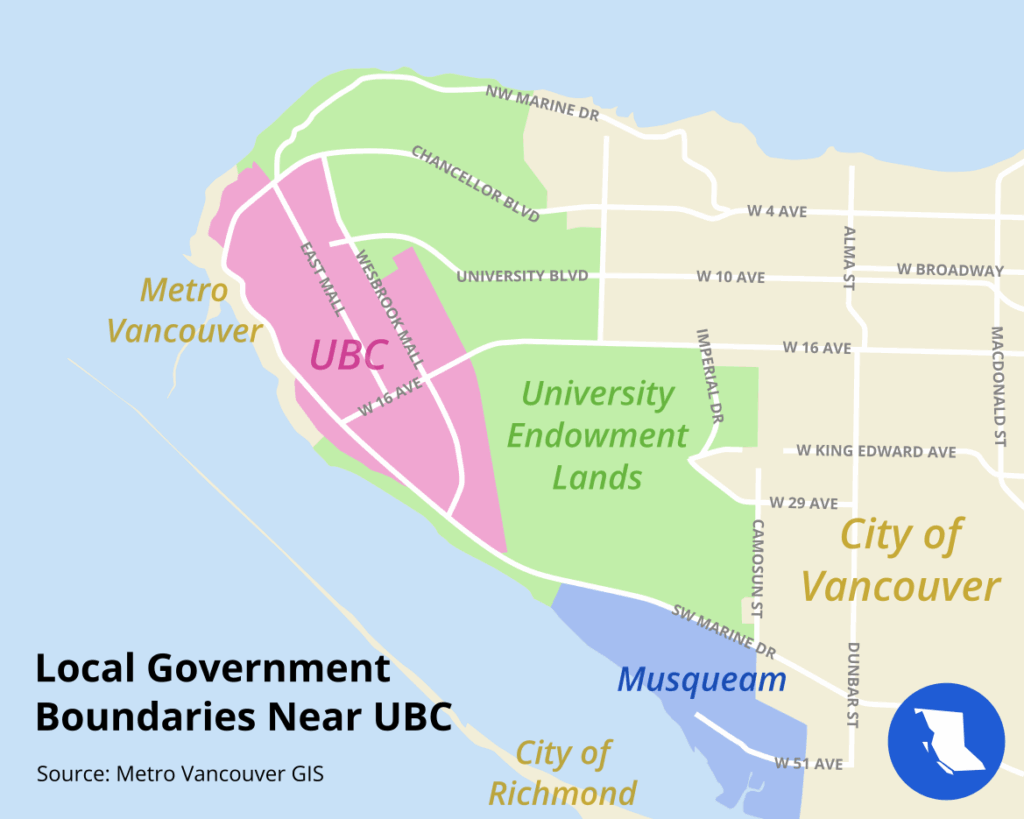

The reason for this is that technically, UBC is not part of any city at all. UBC is actually composed of two non-cities: the University of British Columbia proper, and the University Endowment Lands. Neither of these have ever been part of the City of Vancouver.

A Tale of Two Not-Cities

The site of the UBC campus was composed of provincially-owned Crown land within the boundaries of the (then) Municipality of Point Grey when it was selected by the provincial government in 1910. To make the brand new campus possible, the provincial government came up with a scheme: 175 acres (0.7 sq. km) would be set aside for the university itself, while another 3,000 acres of adjacent land (12.14 sq. km) would be sold off and developed in order to finance the university’s construction.

By the time the university campus was actually completed in 1925, only a small fraction of that land had actually been developed, and a dispute quickly broke out between the province and Point Grey over who could get to benefit from the property tax revenue from the new development, how it should be assessed, and who would be responsible for the cost of the infrastructure.

The province wanted to keep the taxes low to entice possible buyers and for Point Grey to handle the upkeep costs, while the municipality wanted higher property taxes to help with their difficult financial situation and to pay for its own infrastructure improvement.

Negotiations eventually broke down entirely after the province tried to unilaterally make all 3000 acres Point Grey’s problem while keeping the right to sell any of that land without Point Grey’s input and take it out of Point Grey’s jurisdiction. Point Grey’s voters soundly rejected this arrangement in a referendum, so the province duly removed the entire area from the municipality’s jurisdiction.

Property sales remained slow and the onset of the Great Depression ensured they would not pick up anytime soon. Point Grey itself was absorbed by Vancouver in 1929; those initial tracts of developed University Endowment Lands (UEL) land remain most of the developed land today.

The vast majority of the rest, remaining forested, was eventually incorporated into Pacific Spirit Park, and besides some parcels being turned back over to the Musqueam First Nation, the political status of the UEL remains essentially unchanged, 100 years later—provincially owned land outside of any municipality, with around 3,000 residents as of 2021.

The UEL is treated as an unincorporated rural area, with the same legal status as places such as Bella Coola, despite it being part of the third largest urban area in Canada. It is under the direct control of the Ministry of Municipal Affairs, and its residents are not subject to Vancouver’s municipal taxation, with property taxes instead being collected according to the provincial Rural Property Tax branch.

With the exception of the formal creation of Pacific Spirit Park and its handover to Metro Vancouver Regional District jurisdiction in 1989, very little has changed about the UEL’s basic structure over the last century.

However, the territory officially under UBC’s own jurisdiction has seen massive changes over the past few decades. The built-up area has grown to encompass most of the land west of Wesbrook Mall. Much of this has been used for academic facilities, but housing was a relative latecomer.

When one thinks of university housing, the thing that first comes to mind for most people is probably housing for students. Indeed, with UBC’s expansion in the post-Second World War period, students began to be able to live on UBC’s own lands, beginning with the Place Vanier complex for first-year undergraduates in 1960.

But starting in the 1980s the University began to see another way it could use the land it had acquired to raise revenues: Residential development that it could lease to the general public. UBC created the University Properties Trust in 1984 to develop and manage these lands. Its first neighbourhood, Hampton Place, was built in 1989, with more and more neighbourhoods being carved out of the University’s lands over the subsequent decades.

The largest, Wesbrook Village, was built starting in 2005, with high and mid-rise developments continuing to go up on the site. This neighbourhood alone already has around triple the population of the UEL and is certain to grow even further in the future.

As of the 2021 census, UBC’s neighbourhoods host a permanent population of just over 15,000 residents on top of a student population of approximately 14,000. The University’s plans are more ambitious than this. The Campus Vision 2050 land use plan, formally adopted by the Board of Governors in July, aims to double the available housing stock and population over the next 25 years. This plan was predictably somewhat controversial, as big densification projects tend to attract negative attention from residents who like the way things are, but they are also complicated by the fact that residents have very little say in the matter. These neighbourhoods are essentially a company town, where everyone is leasing from the university.

Lacking in Local Government

UBC was not designed to function like a municipality, but it has nonetheless found itself governing more people than many neighborhoods in the City of Vancouver proper and more than some entire Lower Mainland towns and cities, with a population that continues to grow rapidly. The body that controls land use at UBC is the University Board of Governors, of which a controlling proportion is appointed by the province with the remaining seats being elected by constituencies of students, faculty, and staff.

Notably absent is any representation from full-time residents who do not study or work at the university, meaning that any decision taken by the university in their capacity as a de facto municipal government can be carried out regardless of any objections from residents without fear of a meaningful electoral backlash or accountability from them. The closest thing UBC residents have to a vote on their local government is the lone seat for Electoral Area A on the Metro Vancouver board, a seat which in practice is a UBC seat due to how sparsely populated the rest of Electoral Area A is.

But even the Director does not have a direct say in how the area is governed. The MVRD gave UBC the ability to do its own land use planning free from its jurisdiction in 2010, and its direct authority extends predominantly to region-wide infrastructure and planning duties, without more granular authority over how each of its component parts manage themselves, including UBC.

To address the democratic deficit in its neighbourhoods, UBC created a quasi-governmental body called the University Neighbourhoods Association to delegate some responsibility for their management and to act as an advisory body. This is the body that UBC neighbourhood residents went to the polls to elect in November, with a seven-member board voted on from amongst eligible UNA members, open to all who live in the University Neighbourhoods. The UNA operates community centres and cultural programs, as well as parking enforcement and some roadworks. On all other matters, the body is free to voice its opinion to UBC, but UBC is not under any obligation to actually listen to them.

This arrangement may not be sustainable in the long run. As the non-student population continues to rapidly increase, to the point where its projected future population would rival the current populations of municipalities like White Rock and Port Moody, residents could well get fed up with a system that prevents them from having much meaningful input on their local governance, particularly under the confusing dual system of the UEL and UBC run-neighbourhoods wherein a large part of the land is a fief of the province while the remainder is a fief of UBC, which in turn is a fief of the province.

Residents also have no input in the municipal affairs of Vancouver, the city whose goings-on have at least as much of an impact on the lives of UBC residents and possibly even more so than the UBC lands themselves, unless they were to spend their entire lives west of Blanca Street, with the lone exception of the School Board. The Endowment Lands, home to a small and very wealthy population entirely inside a major urban centre and directly subject to provincial administration also feels increasingly like an anachronism in an era where the housing crisis has taken centre stage in provincial politics, and the current government has made urban densification a major pillar of its platform.

Where Do We Go Now?

Considering the length it has taken to explain how local government even works there, as well as the fact that a large proportion of the population are students, it is probably not surprising that the vast majority of the area’s residents don’t bother to engage with its local governance at all. In the 2022 election for Electoral Area A Board Director, 15,000 ballots were sent out to voters but only 1038 were returned, of which 999 were valid. The most recent University Neighbourhoods Association election similarly tallied only 1002 votes. These amount to turnout rates of less than 7%, compared to roughly 30% average turnout for municipal elections across the province. The absence of real power vested in any elected local office surely explains much of these figures, and the UNA and incumbent Director Jen McCutcheon have both expressed frustration at their lack of input in the affairs of their constituencies.

It appears very plausible that change may come one day. The removal of the lands from municipal authority was not intended to be a permanent solution back in the 1920s, and proposals for a different arrangement have gone back decades.

There are two ways that the UBC lands could be placed under municipal authority: One or both of its constituent parts could either be added to the City of Vancouver, or they could be incorporated as its own independent municipality.

Proposals for this began almost immediately after they were detached, but over the previous century none of them have been able to get much momentum behind them. A 1995 referendum on incorporation failed with little fanfare, the only time that the question has been at direct electoral stake. A 2006 report by the Greater Vancouver Regional District recommended annexation by the City of Vancouver, but that also ended up being quietly forgotten. Most recently, the province published a report in 2022 on UEL governance that recommended a move from the status quo to either option, though it declined to recommend one over the other or to establish a timeline. For the time being, any change remains in the realm of the hypothetical.

Just like it was a century ago, the main obstacle is the question of how to pay for the infrastructure and services that would now be offloaded onto either Vancouver or the new municipality.

If the area is incorporated by itself, it would suddenly find itself responsible for its own upkeep and face significantly more financial strain than it currently does. Amalgamation with Vancouver would largely solve this financial question, but as a relatively small drop in a much larger bucket, the UBC area would not have much opportunity to run its own affairs, somewhat defeating the impetus for reform in the first place, though residents might appreciate the chance to vote for Vancouver’s mayorship and city council.

Given that the loudest voices for change are those arguing that the University is building too much too quickly, and that the City of Vancouver’s land use restrictions have resulted in it building new homes at a much slower rate than UBC, it is likely that either scenario would result in UBC’s ambitious building projects being greatly slowed or stopped entirely.

The sudden appearance of skyscrapers out of the forest has been rather jarring to some, raising questions about the wisdom of the university building new full-price market housing. While it could certainly be argued that the University’s current plans do not allocate anywhere close to enough housing exclusively for students or staff, it is difficult to believe that this alternative scenario improves their lot much at all.

If resident concerns reduce the scope of construction as they have in the neighbouring “regular” cities, students or other residents who would otherwise live in the market housing on campus would turn to neighbouring areas, which are uniformly low-density. There, the main options for students are to either gather enough roommates to afford to rent out an entire house, or to find precarious and still-very-expensive space in a grey-market basement suite or similar accommodation.

The extra demand that financially justifies the construction of the high-rises would be turned towards these, bidding up prices for them even further. For these people, the local governance of the UBC neighbourhoods exerts a powerful but invisible force, and this would become even starker if incorporation were to take place, and to a lesser extent with amalgamation. Considering the revenue that this development brings in, the University does not seem to be in any rush to change course, and this may be for the best.

After all, for all the talk of a democratic deficit, both the UEL and UBC are ultimately answerable to a democratic body that residents are fully capable of voting for. It’s one that is also shared with most of the people who work at UBC and most of those who are affected by the same infrastructure, housing market, and labour market that UBC is a part of: the provincial government.

For all the labyrinthine, maddening mess that is UBC’s jurisdiction, any changes to the area’s governance would be initiated by the province, and nothing there can happen without the province’s approval, tacit or explicit. UBC’s bizarre local government remains a curiosity, with the consequences of the university’s free hand being the sprouting of a thicket of high-rises a long way from their closest cousins, but it may be in practice more democratic than it might be if it were under the control of a small circle of local residents worried about what an increase in the number of local residents would bring. If the situation is truly intolerable, these neighbours can take the matter up with one of their other neighbours–local resident, area MLA, and Premier David Eby.

Leave a Reply