Image credit: RealBuizel10 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Nic Laporte and Movement: Metro Vancouver Transit Riders recently released a video discussing the phenomenon of a “transit death spiral”, and the converse positive feedback loop that comes with adequate investment. If you haven’t already seen it, definitely check the video out. As an extension to the topic of that death spiral, however, there is another key element of transit funding that isn’t well known at all – something that industry insiders refer to as “schedule maintenance”.

Transit agencies already face the same cost-inflationary pressures that we all do – things like fuel costs and labour costs have a direct impact on operating costs, which generally track at a similar rate to the inflation experienced by broader society. However, that pesky, inconvenient truth known as schedule maintenance throws an additional wrench into things. If you find inflation to be having a noticeable negative impact on your day-to-day expenses, have you ever imagined what experiencing double, or even triple, the inflation would be like? That’s the reality that transit agencies are experiencing, year over year.

So what exactly is it? Simply put, schedule maintenance is an ongoing necessary investment to maintain the quality of your transit service over time, protecting it from factors that slow down your service, including worsening traffic congestion, as well as increases in dwell time over time as ridership grows.

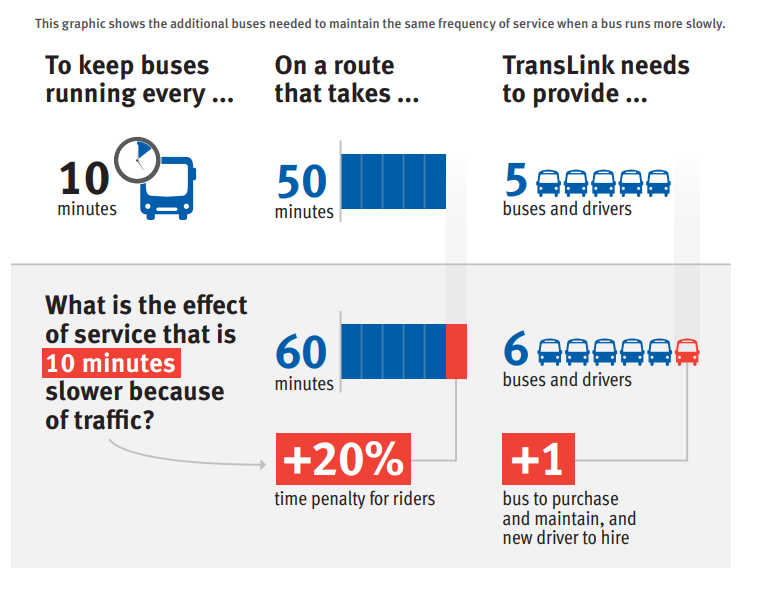

Here is an example, from TransLink’s Bus Speed and Reliability Report, but expanded further.

Suppose you had a bus route that could be completed in 50 minutes. In order to provide service every 10 minutes, you require 5 buses (and drivers) to operate that route. Your overall cost, assuming 8 hour shifts, is approximately 40 service hours, where you’re paying for 5 buses (and drivers) for 8 hours each.

Now, suppose congestion became worse, and that 50 minute trip now requires 60 minutes to complete. In order to provide that same 10 minute service, you now require a 6th bus (and driver) on the route. Your overall costs have increased from 40 to 48 service hours, as you now have to pay a 6th driver for those same 8 hours. That 20% increase is the cost of schedule maintenance: where a constant injection of resources over time is required simply to maintain existing service levels.

Now, here’s what TransLink’s example doesn’t include.

What if the service hour budget was frozen, and you only have the same 40 service hours to work with?

On that route that now requires 60 minutes to operate, where you only have enough funding to operate 5 buses on the route, you are now only able to provide service every 12 minutes. To a transit rider, that represents a substantial reduction in the amount of service, which will extend wait times and exacerbate overcrowding, despite no change to the required service hour budget.

Taking this further, imagine if your operating budget itself has been frozen, despite required costs per service hours increasing by 20% over time due to external pressures? You are now only able to afford to pay for 4 buses to operate on this route that now requires 60 minutes to complete, with service now reduced to only operate every 15 minutes. This compounding of cost inflations in this instance has now yielded a net capacity cut of a third of what had previously been provided.

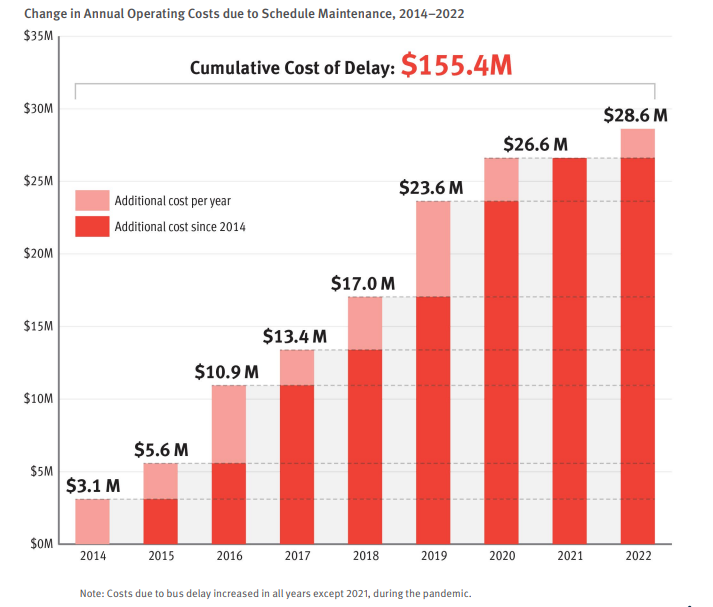

The effects of this “compounding inflation” can be seen clearly here. TransLink’s schedule maintenance needs over the last decade have directly caused the operating budget to increase by hundreds of millions of dollars. Imagine what our transit service could have looked like if that budget had been used on service expansion instead.

All of the above cases can hinder the attractiveness of a transit service, even in the case where resources are invested to maintain headways. The slower speeds and natural increases in variability over time can hinder the attractiveness of a transit service, even if headways are maintained. Riders may find that the service has become less reliable, or that the increases in trip time have actually broken a key connection somewhere in their transit journey, drastically extending their overall required trip time even though service levels do not appear to have changed.

Another factor as well is the natural ridership growth associated with population growth, that may cause worsening overcrowding. Even in cases where headways have been maintained as services become slower, increased ridership could mean that the capacity that’s provided is no longer adequate for the demand the service has, increasing the risk of overcrowding, or worse, pass-ups. As a transit rider, there is no greater sense of betrayal than watching a bus come up to your stop, only for it to drive past without stopping while flashing SORRY BUS FULL. As an agency, the only way to mitigate that is with an ongoing injection of resources to improve service levels just to prevent overcrowding from becoming a bigger problem as ridership continues to grow. When you already have widespread overcrowding, it’s arguably already too late.

Without adequate investment to address the above issues, transit services will begin to fall into that negative feedback loop of a ridership death spiral, as natural degradation in service quality reduces how attractive the service is. Whether it be from worsening passenger comfort through overcrowding, lengthened overall trip durations from slower speeds and broken connections, or from worsened on time performance due to increased traffic volatility, some passengers may decide to simply stop taking transit and switch to another mode such as driving, further increasing traffic congestion on the road, while also removing valuable fare revenue from a transit agency’s bottom line.

The reality is, transit requires a constant increase in funding simply to maintain service levels and service quality. Budget increases are required to accommodate inflationary pressures on the cost per service hour provided, and on top of that, additional service hours are also required to perform schedule maintenance. A stagnant service hour budget is equivalent to regression, where transit agencies are faced with the difficult decision of needing to cut service simply to find the resources required for “business-as-usual”.

We can see how this very real problem has impacted transit services in our province – using examples from the two largest systems in the province.

A Tale of Two Systems

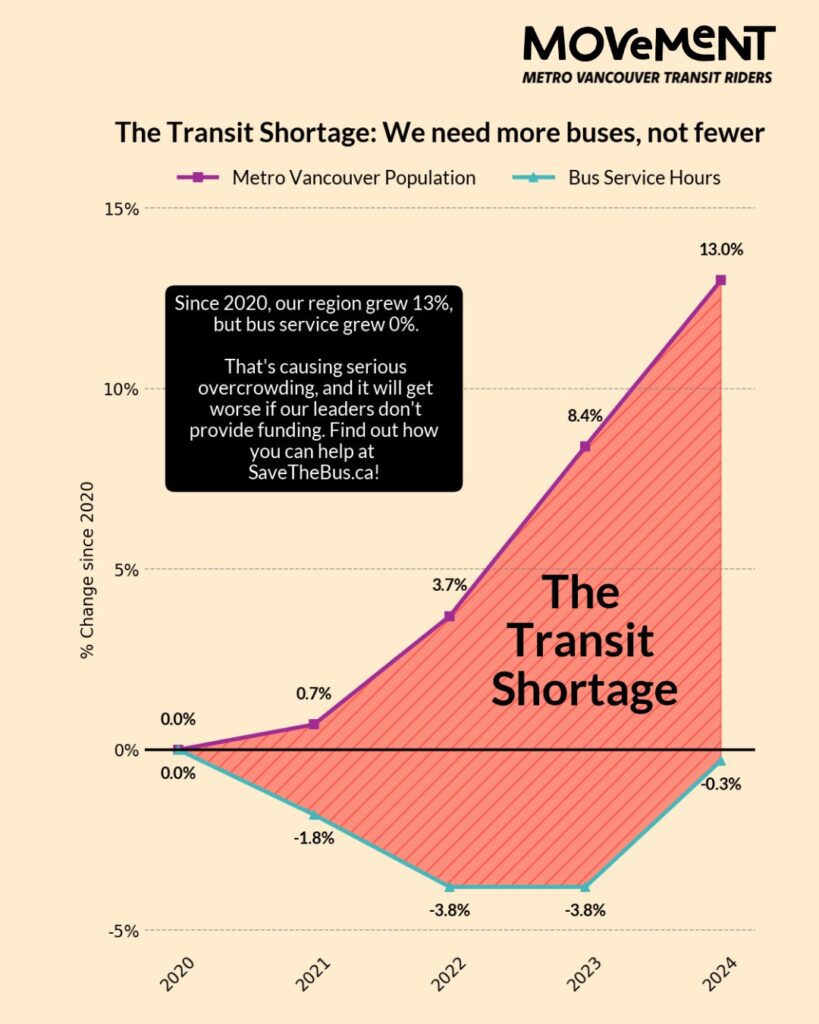

From before COVID, until last year, TransLink’s total bus service hours had increased by approximately 120,000 annually, or approximately 2%. However, that increase is entirely attributed to the cost of schedule maintenance. Once schedule maintenance is excluded, bus service hours in 2024 were actually lower compared to 2020, despite a 13% increase in Metro Vancouver’s total population.

The expansion included in the 2025 Investment Plan, to the order of a 5% increase in service, is a significant step towards addressing this gap, but it’s nevertheless far from enough to make up this shortfall.

In Victoria, a limited budget for service maintenance demonstrates the other extreme. The Victoria Regional Transit System’s current service hour budget is approximately 5% higher than what had been budgeted in 2019-2020. However, buses are less frequent and slower than they were six years ago. Most branded Frequent Transit Network (FTN) routes have lost their 15 minute service standard on evenings and weekends, while certain routes, such as the 2/5 and the 11, have seen service levels completely decimated. The entirety of the planned expansion for the next fiscal year is budgeted for service maintenance needs, and even that is insufficient, requiring additional service cuts to other high-ridership routes. The schedule maintenance monster continues to gobble up frequent routes, making them both less frequent and slower.

When budgeting for transit’s operational expenses, generally speaking, ensuring that the “base budget” is funded is typically a pretty ironclad minimum requirement, but even that can include multiple different scenarios, with vastly different levels of impact:

- Maintaining the same dollar figure for the “base budget” is, in practice, a devastating service cut that could see entire communities cut off from reliable transit services altogether, as the same amount of money is unable to keep up with inflationary pressures, and is no longer able to pay for even the same amount of service hours. The doomsday fiscal cliff scenarios generally fall under this category.

- Maintaining the same amount of service hours still means a gradual erosion of service quality due to schedule maintenance needs. This is similar to the trends seen in Victoria, where service levels largely remained stagnant over the last few years.

- Accounting for schedule maintenance needs as part of the base budget, which means a small gradual increase in actual service hours. This is similar to what had come to pass in Vancouver between 2020 and 2024, where while there was a marginal increase in the total number of service hours, all of that had gone towards maintaining service levels.

So, what can we do instead?

For transit to truly succeed, ambitious investments towards improving the service is required. In addition to increases in transit budget, both capital and operational, to provide more service on top of schedule maintenance needs, transit priority is also another key area for improvement that can rapidly yield tangible benefits for the community as a whole, all while keeping the schedule maintenance monster under control.

The fundamental concept of transit priority is to direct a one-time capital expenditure towards a project intended to speed up transit vehicles, yielding ongoing operational savings. In addition to counteracting the natural degradation of your transit service (and thus counteracting the need for schedule maintenance), transit priority, if implemented correctly, can even generate further savings beyond that. This could be seen as a way to reduce necessary operational expenses over time – transit priority projects typically pay for themselves within a few years, and everything after can be considered a net savings – or those savings can be redirected straight into service improvements.

A great example of the benefits of transit priority can be seen on Marine Drive in Vancouver. In Spring 2023, TransLink launched the Route 80 Marine Drive Express service, funded entirely by operational savings generated by bus stop balancing, a measure in the transit priority toolkit where buses are sped up by adjusting the spacing between individual bus stops and addressing cases where a bus is stopping too frequently. Despite launching with only peak-period service to start, this new service became an immediate success, and TransLink will be implementing midday service on the 80 next month to build upon that success.

The 80 is a fantastic example of how transit priority measures, as well as service expansion funding, can create meaningful benefits for transit users, kickstarting a positive ridership feedback loop, where improved service attracts more people onto transit, leading to positive societal outcomes such as improvements to congestion, which then incentivizes further service improvements. That ongoing investment to keep the positive feedback loop going (staving off the negative death spiral in the process) is essential to the success of our transit networks, and thus essential to the success of our communities as a whole.

Leave a Reply